The Importance of Prescribed Burning

Regular low fire intensity burning of litter and undergrowth under mild weather conditions offers the only practical way of reducing fuels in forest and woodland. Other approaches have been suggested, such as mechanically removing litter and undergrowth, but have not proved to be practical orcost-effective. Mechanical slashing may be useful in heathland or low scrub vegetation, but not in most forest or woodland.

Fire in heavy litter like this is impossible to control in hot,windy weather

Low intensity burning has a number of incidental benefits to the forest ecosystem. Nutrients locked up in slowly decomposing woody material are released and re-enter the forest nutrient recycling system. While some nitrogen is lost to the atmosphere, it is counterbalanced, in nature’s way, by the stimulation of regeneration of nitrogen-fixing leguminous understorey plants. It has also been shown that some plant species depend on the smoke from fires to stimulate germination.

A low intensity burn in jarrah forest

A crucial issue now is the level of fuel reduction burning required to provide the level of protection that was achieved over the period 1962-2000. Over the period 1962-1995 the annual area of burning fluctuated in response to seasonal weather conditions, but averaged about 300,000 ha a year of the total of about 2,500,000 ha of forested land in the southwest. In this context, the forested land includes other ecosystems within the forest envelope, such as rocky outcrops, swamps and flats.

In the jarrah forest types, the burning rotation varied from 5-7 years, according to site, but was only about three years in the vicinity of towns, valuable assets like plantations and important infrastructure. Changes in the silvicultural system used in jarrah that were associated with procedures to restrict the spread of jarrah dieback disease led to more concentrated timber harvesting. It became necessary to withhold fire for a longer period to protect the regrowth until it could tolerate a low intensity fire. DEC set this period at 20 years, which BFF believes is excessive. Regrowth forest has been successfully burned under mild conditions as early as 6 years in the past.

In karri forest types, the burning rotation was necessarily longer, 8-12 years, with even-aged karri regeneration protected from fire for up to 30 years. This withholding period can be reduced if the regrowth forest can be thinned, for example, for pulpwood, at age 20-25. Currently, the thinning program seems unable to keep pace with requirements.

A karri regrowth thinning operation – an essential factor in improved fire protection in southern forests.

A low intensity fuel reduction burn in karri-marri forest

Over the years 2000-2015, the level of fuel reduction burning by DEC (and PAW subsequently) declined drastically and average fuel loads increased markedly. A large backlog has built up in that time. Current DEC/PAW policy is that an annual area of burning of 200,000 ha is sufficient to provide adequate protection against large wild fires.

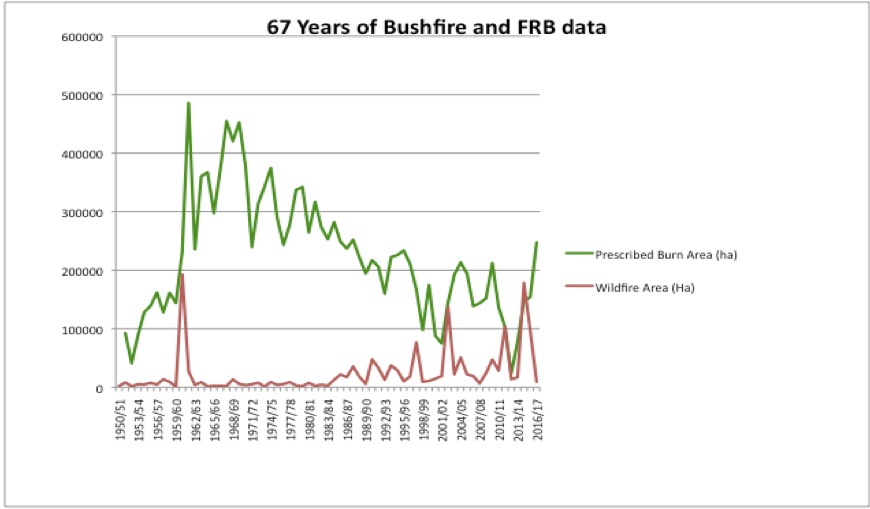

There is no scientific basis for this policy. It is not supported by the experience of the last 40 years, which indicates that anaverage annual burn area of 300, 000 ha is necessary. The graph below shows how the area of burning has varied since 1955. The large decline in area in the period 1996-2002 has resulted in the accumulation of a backlog of almost 500,000 hectares. The increase in area after 2003 is encouraging, but still inadequate.

The area of prescribed (fuel reduction) burning is shown in green, and the area of bushfires (wildfires) in red.

On DEC’s own (CALM) data, over 60% of the forest area of the southwest contains fuel loads at which direct attack will fail under only moderately severe weather conditions. The Muller report to CALM in 2001 clearly outlines this problem and also highlights the longer response times to get to a fire outbreak, due partly to the downgrading of some district offices, and partly due to closure of forest access roads. In this context, the planned closure of even more roads in areas proposed to become wilderness areas is of great concern.

Forest with high fuel loads raises the important issue of safety of firefighters.

The higher the fuel load the greater the fire intensity and the more erratic fire behaviour becomes. Firefighting is inherently a dangerous activity at the best of times, but we are significantly raising the risk to this vital component of the fire management system as fuel loads increase. Already, there are reports of volunteer bush fire brigades expressing unwillingness to assist DEC/CALM in fighting fires in some areas, due to the perceived risks involved.

Fighting a fire like this is a very dangerous business! (Photo K White)

Sometimes things do go wrong…..

It is claimed by some that the previous approach to forest firemanagement, based on regular fuel reduction burning, has adverse effects on biodiversity. Such claims do not recognize the diversity of fire intensity that occurs in a burn under mild conditions, nor the fact that about 30% of the area remains unburnt. It is notable that one rarely sees a person engaged in, or experienced in, on-ground forest management making such a claim.

The requirement for some plant species for a certain period of time before they can set viable seed is often advanced as a reason why there should be no burning at all, or at least much longer burning rotations. While this may be a problem in theory, no one has ever been able to document any practical adverse effects of this kind. In fact, the very comprehensive biodiversity studies undertaken in association with the Regional Forest Agreement process indicated that no known component of forest biodiversity had been lost from Western Australian forests. At the present time there is no scientific evidence that the previous fuel reduction burning program has had any adverse effect on biodiversity.